Reflections of Colorblindness

By Mollie Innocent-Cupid, Deputy Executive Director

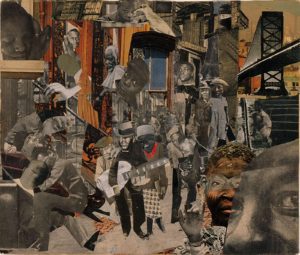

As we continue to celebrate Black History Month, I always find the urge to remind myself that Black History is American History. And if I’m being honest, and if I had it my way, there would be no need for Black History Month because the stories, struggles and successes of Black Americans would be interwoven into every aspect of our education and society. Just as we all somehow learned about George Washington’s wooden teeth, it would have been nice to also learn about Juneteenth, or the Tuskeegee Airmen, or Ruby Bridges too.

But… we’re not quite there yet. In an eagerness to achieve a state of colorblindness, we have taken a fascinating turn of deliberately censoring and erasing the racial history of America. Just last year a veteran was silenced when speaking about the origin of Memorial Day: birthed from a custom of freed Black slaves who honored soldiers who had passed away during the Civil War. So, the question that must be asked is, “Why?”

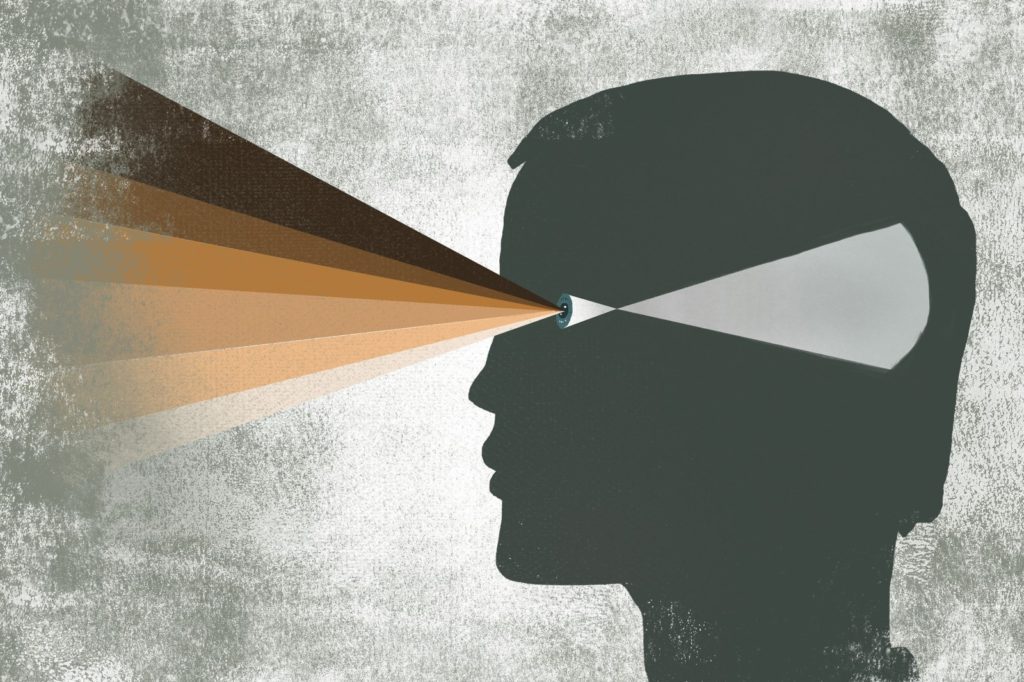

Colorblindness allows us to take away the sting of the past, the discomfort of the ugliness of how one human treated another. It’s comfortable, and enables us to see no race, and therefore not confront any of the issues that emerge due to race. And let me pivot for a moment if you’ll allow — the Christian lens of “We are all God’s children” tends to promote this same mentality and approach. Yes, we are brothers and sisters through Christ, and though our faith serves to unite us, it must not serve to erase our identities or the different injustices that are experienced. It must not deny us our capacity for empathy or understanding.

Did you know that children are aware of racial differences by the age of five? We know that race is not something that you can simply “unsee.” Instead, in choosing to be colorblind we are willfully choosing to ignore something that the world sees and reacts to. It’s intentionally choosing not to acknowledge the identity of the person across from you. And the question here is, “Why?”

So, as we celebrate and acknowledge the amazing representatives of Black History (both past and present), such as “the first Black man to get a PhD from Harvard” and “the first Black woman to run for president,” and “the first Black principal dancer at the American Ballet Theatre” we must also acknowledge the struggles and criticism and challenges that they faced to get there. We can’t celebrate the success without acknowledging the struggle, without sitting in reflection of the blatant racism and obstacles every step of the way. That, to me, is where the true inspiration lies.

I’d like to share a moment I had years ago with one of my mentors as a young clinical director: I was speaking with him (a White man, for context) about some of my challenges with making changes in the organization, with some of my ideas being dismissed as not do-able. He paused for a moment, and responded, “Well, as a young Black woman in a new leadership role, you have to navigate through some additional challenges…” He then continued to advise me about next steps, and provided me with the guidance and mentorship that he always did. Long story short, in that moment, although I was not actively thinking about my race nor my gender, he comfortably brought it in the room, allowing it to be acknowledged while recognizing how his lived experiences have differed from mine.

My final question: How does omitting race/ethnicity impact your shared spaces, and how does acknowledging it and naming it impact that space?